, OH

One of America’s largest and best known steam locomotive builders, the Lima Locomotive Works built 7,752 locomotives between 1879 and 1951. It rose to success building the patented Shay geared locomotive, an innovative design that became the standard for railroad logging. In the early 20th century Lima began building mainline locomotives, exemplified by the “Super-Power” 2-8-4 Berkshire, which used superheated steam and an enlarged firebox for unprecedented power and speed. Introduced in 1925, it showcased Lima’s technological prowess. The “loco works” employed workers of many nationalities, fostering a legacy of ethnic diversity in Lima. Often several generations of the same family worked in the same shop, a practice that encouraged loyalty and a tradition of craftsmanship passed to succeeding generations.

, OH

Charles E. Wilson was born on July 18, 1890 in Minerva. After earning a degree in electrical engineering from the Carnegie Institute of Technology in 1909, he joined the Westinghouse Electric Company in Pittsburgh before moving to General Motors in Detroit in 1919. By January 1941, Wilson had become president of General Motors, and during World War II directed the company’s huge defense production efforts, earning him a U.S. Medal of Merit in 1946. While still with General Motors, President Dwight Eisenhower selected him as secretary of defense in January 1953. During his confirmation hearings, Wilson said, “What was good for the country was good for General Motors and visa versa,” but was interpreted as saying solely, “What’s good for General Motors is good for America.” He served Eisenhower for four years, reorganizing the department of defense to effectively deal with missile and nuclear technology. He died in Norwood, Louisiana, on September 26, 1961.

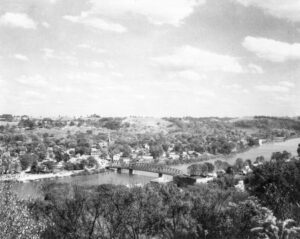

, OH

Luke Chute is the site of an early mill that harnessed river power. About 1815, Luke Emerson and Samuel White built a dam part way across the river. This created a rapid between the shore and the end of the dam, the chute. Here they constructed a mill to grind grain. The system of locks and dams built on the river from 1836 to 1841 not only made the Muskingum River navigable by steamboats, but also harnessed the power of the river. After 1841, at least one mill was located at most of the dams. Water power encouraged industry in the Muskingum Valley.

, OH

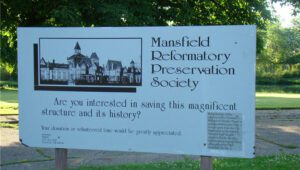

Designed by architect Levi T. Scofield, the Ohio State Reformatory opened its doors in 1896 as a facility to rehabilitate young male offenders through hard work and education. A self-sufficient institution with its own power plant and working farm, the reformatory produced goods in its workshops for other state institutions and provided opportunities for inmates to learn trades. As social attitudes towards crime hardened in the mid-twentieth century, it became a maximum-security facility. The six-tier East Cell Block is the largest known structure of its kind. Considered substandard by the 1970s, The Ohio State Reformatory closed in 1990. It has served since as a setting for several major motion pictures. This Mansfield landmark was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1983.

, OH

When St. Paul’s Methodist Episcopal Church was dedicated on January 6, 1884, an ornate brass chandelier presented by the Edison Electric Light Company provided illumination for the ceremony. Wired for electric lighting before its completion, St. Paul’s was one of the first churches in the nation lighted by Edison lamps. The Tiffin Edison Electric Illuminating Company, the first central electric power station in Ohio and the tenth in the United States, was built in Tiffin in late 1883. With a 100 horsepower boiler, a 120 horsepower engine, and two dynamos, it supplied direct current sufficient to light 1,000 lamps. It stood two blocks north of this site. The original brass “electrolier” still hangs in the sanctuary inside.

, OH

Like many nineteenth century communities in Ohio, Stryker owes its birth and early growth to the railroad industry. Stryker, named for Rome, New York, attorney and railroad executive John Stryker, was surveyed on September 19, 1853, beside the proposed Northern Indiana Railroad. For more than fifty years, “track pans” at Stryker allowed steam locomotives to take on 5,000 gallons of water while traveling at forty to fifty miles per hour, saving valuable time, “the principal enemy of railroad schedules.” On July 23, 1966, the U.S. rail speed record of 183.85 miles per hour was set through Williams County, including through Stryker. The Stryker depot was constructed in 1900 and placed on the National Register of Historic Places on August 7, 1989. (continued on other side)

, OH

In 1922, during the infancy of broadcast radio, the call letters WLW were assigned to the station begun by Cincinnatian Powell Crosley Jr. The station moved its transmitting operations to Mason in 1928, and by April 17, 1934, WLW had permission to operate experimentally at 500,000 watts. Becoming the first and only commercial radio station to broadcast at this “superpower,” WLW was formally opened at 500,000 watts by President Franklin D. Roosevelt on May 2, 1934. Using its 831-foot Blaw-Knox antenna to broadcast at ten times the power of any station, it earned the title “The Nation’s Station.” Locals reported hearing broadcasts on barbed wire fences, milking machines, rainspouts, water faucets, and radiators. The custom built transmitter, a joint venture between RCA, GE, and Westinghouse, remained in operation until March 1, 1939 when the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) ordered the station to return to broadcasting at 50,000 watts.

, OH

Completed in 1837, the limestone lock nine served as a catalyst for the growth of Piqua. The lock helped connect the village to Cincinnati (1837) and Toledo (1845) by way of the Miami and Erie Canal. German immigrants traveled up the canal from Cincinnati and settled within a five-block area of the lock. Industries used the lock as a source of water power and developed products as diverse as flannel, flour, and flax seed. Lock nine remained as a functioning part of the canal until its destruction during the flood of 1913.