, OH

Opened in July 1862, the 35 1/2-acre site here in Brooklyn Township’s University Heights served as the largest Civil War army camp of rendezvous, organization, and training in northeast Ohio. It was bordered by Hershel (now West 5th) and University (now West 7th) streets and Railway and Marquard avenues. A wartime high of 4,151 volunteers occupied the barracks here on December 5, 1862. Lieutenant William Dustin of the 19th Ohio Volunteer Artillery wrote, “It was a table land above the city and admirably suited to the use of a camp of instruction. It was as level as a floor and carpeted with grass. The capacious pine barracks held about 25 each of the battery’s men.” A total of 15,230 men trained here during the war–4.9 percent of the 310,646 enlistments in Ohio. More than 11,000 soldiers were discharged here at war’s end. It closed in August 1865. (continued on other side)

, OH

Isaac Campbell Kidd, Sr. was born in Cleveland in 1884. He entered the United States Naval Academy in 1902 and dedicated his life to the Navy. While an ensign, he sailed around the world with the “Great White Fleet” from 1907 to 1909. During the 1920s and 1930s, he held numerous flag commands. Promoted to Rear Admiral in 1940, he was assigned as Commander, Battleship Division ONE. On December 7, 1941, Kidd was aboard the battleship USS Arizona in Pearl Harbor, Hawaii. During the surprise Japanese air raid, bombs detonated her ammunition. The resulting explosion sank the ship, causing the loss of 1,100 crewmen, including Admiral Kidd. He was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor for his bravery. Two destroyers were named in honor of this World War II naval hero: USS Kidd (DD-661), 1943-1964 (still afloat as the centerpiece of the Louisiana Naval War Memorial, Baton Rouge), and USS Kidd (DDG-993), 1981-1998.

, OH

The Sarah Benedict House is a rare survivor of the once fashionable Upper Prospect neighborhood that included “Millionaires Row” on adjacent Euclid Avenue. Sarah Rathbone Benedict had this Queen Anne-inspired house built in 1883, when she was 68, and lived here until her death in 1902. She was active in the social, religious, and charitable life of Cleveland. Sarah Benedict was the widow of George A. Benedict, editor of the Cleveland Daily Herald. The house was given to the Cleveland Restoration Society by Dr. Maxine Goodman Levin in 1997 and rehabilitated for its headquarters in 1998. It is listed in the National Register of Historic Places and contributes to the locally designated Prospect Avenue Historic District.

, OH

One of the most recognized figures of the Harlem Renaissance, Langston Hughes was born in Joplin, Missouri on February 1, 1902 and moved to Cleveland by the time he was in high school. An avid traveler, he credited his years at Central High School for the inspiration to write and dream. The consummate Renaissance man, Hughes incorporated his love of theater, music, poetry, and literature in his writings. As an activist, he wrote about the racial politics and culture of his day. He was awarded the Spingarn Medal by the NAACP. He published over 40 books, for children and adults. Known as the “Poet Laureate of the Negro People,” Hughes most famous poem is “The Negro Speaks of Rivers.” Langston died on May 22, 1967, and his remains were interred beneath the commemoratively designed “I’ve Known Rivers” tile floor in the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture in Harlem.

, OH

Following the national merger of the American Federation of Labor (AFL) and the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) in 1955, more than 2,000 labor delegates representing one million union members convened at the Cleveland Public Auditorium for the founding convention of the Ohio AFL-CIO in 1958. This leading labor organization achieved significant advances in the quality of life and security for working Ohioans during the second half of the twentieth century in areas of civil rights, workers’ compensation, and unemployment insurance. Its notable legislative successes include the passage of a public employee collective bargaining bill in 1983 and a voter referendum that protected worker’s compensation in 1997.

, OH

Organized efforts to establish an eight-hour workday existed as early as 1866 in the United States. The Cleveland Rolling Mills Strikes of 1882 and 1885, as part of this almost-70-year struggle, contributed to the establishment of the eight-hour workday. Both strikes challenged the two-shift, twelve-hour workday in addition to seeking recognition of the Amalgamated Association of Iron, Steel, and Tin Workers. The first strike – by English, Welsh, and Irish skilled workers – was at the Newburgh Rolling Mills, a major producer of steel rails for the rapidly expanding railroad industry that once stood near this site. It was quickly broken when unskilled Polish and Czech immigrants, unaware of the ongoing labor dispute, were hired. The strike ended when these new workers did not support the union. (continued on other side)

, OH

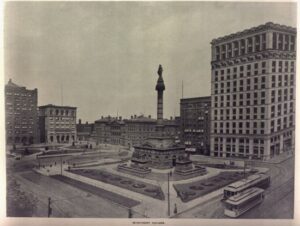

This monument, dedicated July 4, 1894, honors Cuyahoga County men and women, who performed military and patriotic duties during the Civil War (1861-1865). William J. Gleason (1846-1905), army veteran and local businessman, proposed its creation in 1879. Captain Levi Tucker Scofield (1842-1917), Cleveland architect and sculptor, designed the structure and supervised its 19-month construction by contractors, A. McAllister and Andrew Dall. George T. Brewster of Boston and George Wagner of New York, professional artists, assisted Scofield as sculptors. A 12-member Monument Commission, appointed by Governor Joseph B. Foraker in 1888, oversaw the project, which included the removal of William Walcutt’s 1860 marble statue of Commodore Oliver Hazard Perry from the site. The monument’s cost of $280,000 was raised by a countywide property tax levy. An 11-member commission maintains the monument funded by the county. (continued on other side)

, OH

The town of Bedford was settled in 1837. Early residents, Hezekiah and Clarissa Dunham donated the land that serves as Bedford Public Square. The Dunhams built one of the area’s first homes in 1832, which stands at 729 Broadway with the letters H & D above the doorway. Early settlers were attracted to the area by the abundance of natural resources and a large waterfall for mill sites. Bedford also served as a stagecoach stop on the route from Cleveland to Pittsburgh. The road or Turnpike Road as it was called was originally part of the Mahoning Indian Trail. By 1895 the road was renamed Main Street (and later Broadway) when the Akron, Bedford, and Cleveland Railway Company (ABC) traversed the middle of the street carrying passengers. The interurban is called “America’s first high speed long distance electric interurban” with speeds in excess of 60 miles per hour. [continued on other side]