, OH

James Cleveland Owens was born in Alabama in 1913 and moved with his family to Cleveland at age nine. An elementary school teacher recorded his name “Jesse” when he said “J.C.” It became the name he used for the rest of his life. Owens’ dash to the Olympics began with track and field records in junior high and high school. Owens chose The Ohio State University without scholarship, supporting himself by working many jobs, including one in the University Libraries. The pinnacle of his sports career came at the 1936 Berlin Olympics, where he won four gold medals, frustrating Adolf Hitler’s attempt to showcase Aryan superiority. After his return, Owens found work as a playground director in Cleveland beginning his life work with underprivileged youth.

, OH

The West Park African American community began in 1809 with the first black settler and one of the earliest residents of the area, inventor and farmer George Peake. With the growth of the railroad industry, African Americans were encouraged to move into the area to work at the New York Central Round House and Train Station located in Linndale. First among these, in 1912, were Beary Frierson and Henry Sharp. As more and more African Americans came, African American institutions followed. In 1919, Reverend Thomas Evans and the families of Herndon Anderson and Joseph Williams founded St. Paul A.M.E. Church, the first black congregation on Cleveland’s West Side. Reverend D.R. Shaw, the Ebb Strowder family and Iler Burrow established the Second Calvary Baptist Church in 1923. Both became pillars of the community.

, OH

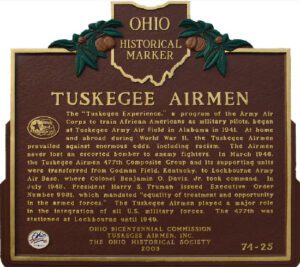

The “Tuskegee Experiment,” a program of the Army Air Corps to train African Americans as military pilots, began at Tuskegee Army Air Field in Alabama in 1941. At home and abroad during World War II, the Tuskegee Airmen prevailed against enormous odds, including racism. The Airmen never lost an escorted bomber to enemy fighters. In March 1946, the Tuskegee Airmen 477th Composite Group and its supporting units were transferred from Godman Field, Kentucky, to Lockbourne Army Air Base, where Colonel Benjamin O. Davis, Jr. took command. In July 1948, President Harry S. Truman issued Executive Order Number 9981, which mandated “equality of treatment and opportunity in the armed forces.” The Tuskegee Airmen played a major role in the integration of all U.S. military forces. The 477th was stationed at Lockbourne until 1949.

, OH

John T. Crawford (1813-1880), was a white Union soldier. In gratitude for the kindnesses he received from African-Americans during the Civil War, Crawford willed his 18 1/2-acre farm to be used as a “home, for aged, indigent worthy colored men, preference to be given to those who have suffered the miseries of American Slavery.” The Crawford Old Men’s Home opened in 1888 and operated until 1964 under the trusteeship of prominent African-Americans such as lawyer William Parham, newspaper editor Wendell Dabney, and Ambassador Jesse D. Locker. It merged with the Progressive Benefit Society’s Home for Colored Women to become the Lincoln Crawford Nursing and Rehabilitation Center. Pleasant Hill Academy, College Hill Library, and Crawford Commons are all on the site of the Crawford farm.

, OH

The National Italian Catholic parish of Saint John the Baptist was founded in October 1896 by the Reverend Father Alexander Cestelli, D.D. Father Cestelli was born in Fiesole, Italy and came to America in 1888 to serve as a professor at St. Paul’s Seminary in Minnesota. In January 1896, founding Rector Monsignor John Joseph Jessing invited Father Cestelli to serve at the Pontifical College Josephinum in Columbus, Ohio as a professor of moral theology. In October 1896, the Right Reverend John Ambrose Watterson, D.D., Bishop of Columbus, appointed Father Cestelli as pastor of the Italian Catholic community. Sunday Mass was celebrated in the baptistery of Saint Joseph Cathedral until September 18, 1898, when the Most Reverend Sebastiano Martinelli, Apostolic Delegate to the United States, dedicated this historic church.

, OH

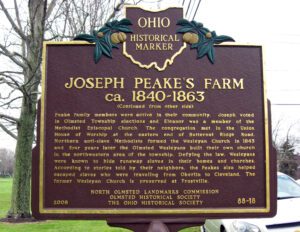

Joseph Peake was born in Pennsylvania in 1792 and came to Ohio in 1809 with his parents and brother. They were the first African Americans to settle permanently in the Cleveland area. He was the son of George Peake, a runaway slave from Maryland, who fought on the British side at the Battle of Quebec in 1759 during the French and Indian War. A man with some means and talent, George Peake invented a stone hand mill for grinding corn, a labor-saving device that endeared the Peakes to their neighbors in western Cuyahoga County. Joseph Peake and his wife Eleanor, an African American from Delaware, bought land in the 1840s on the Mastick Plank Road and built a home near this marker. [Continued on other side]

, OH

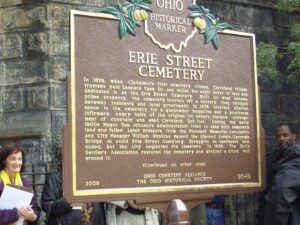

In 1826, when Cleveland’s first cemetery closed, Cleveland village trustees paid Leonard Case Sr. one dollar for eight acres of land and dedicated it as the Erie Street Cemetery. Built on what became prime property, the cemetery touched off a century long struggle between residents and local government. In 1836, trustees allotted space in the cemetery for a gunpowder magazine and a poorhouse infirmary. Angry heirs of the original lot owners claimed infringement of covenant and sued Cleveland, but lost. During the early 1900s Mayor Tom Johnson’s administration tried to take back cemetery land and failed. Later pressure from the Pioneers’ Memorial Association and City Manager William Hopkins caused the planned Lorain Carnegie Bridge to avoid Erie Street Cemetery. Struggles to confiscate land ended, but the city neglected the cemetery. In 1939, The Early Settler’s Association restored the cemetery and erected a stone wall around it. (continued on other side)

, OH

“Lifting As We Climb”: The Cincinnati Federation of Colored Women’s Clubs (CFCWC) was organized May 6, 1904, during a meeting called by Mary Fletcher Ross at the Allen Temple A.M.E. Church. Gathering together eight existing African-American women’s clubs, the CFCWC sought to unite in their work promoting “the betterment of the community.” At a time when both government and private philanthropies overlooked the needs of Black Americans, CFCWC members helped to organize the city’s first kindergartens for Black children, taught in Cincinnati African-American public schools –including the Walnut Hills Douglass and Stowe schools—and raised money for the Home of Aged Colored Women. Since 1904, the Cincinnati Federation of Colored Women’s Clubs has ensured the civic and constitutional rights of all African Americans while meeting the needs of their city.