, OH

In 1804, Enoch (1764-1817) and Achsah (c.1767-1839) Carson and their seven children journeyd from New Jersey to Cincinnati. In 1805, they settled in the western hills in a large grove near Beech Flats, in what would become Green Township in 1809 and Cheviot in 1818. Game was plentiful and fertile soil yielded abundant crops. By 1806, Carson had cleared and cultivated nearly 20 acres of his land. That fall, he began a tradition that has continued into the 21st century. Echoing the ancient custom of harvest home, Carson brought together a fledging community to celebrate its good fortune and abundant harvests. Each passing year the community gathered in Carson’s grove to give thanks, rejoice, and uphold the tradition of harvest home. (Continued on other side)

, OH

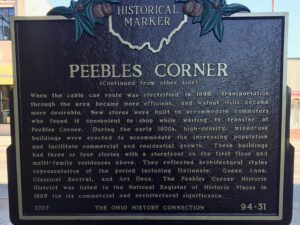

When the cable car route was electrified in 1898, transportation through the area became more efficient, and Walnut Hills became more desirable. New stores were built to accommodate commuters who found it convenient to shop while waiting to transfer at Peebles Corner. During the early 1900s, high-density, mixed-use buildings were erected to accommodate the increasing population and facilitate commercial and residential growth. These buildings had three or four stories with a storefront on the first floor and multi-family residences above. They reflected architectural styles representative of the period including Italianate, Queen Anne, Classical Revival, and Art Deco. The Peebles Corner Historic District was listed in the National Register of Historic Places in 1985 for its commercial and architectural significance.

, OH

“Lifting As We Climb”: The Cincinnati Federation of Colored Women’s Clubs (CFCWC) was organized May 6, 1904, during a meeting called by Mary Fletcher Ross at the Allen Temple A.M.E. Church. Gathering together eight existing African-American women’s clubs, the CFCWC sought to unite in their work promoting “the betterment of the community.” At a time when both government and private philanthropies overlooked the needs of Black Americans, CFCWC members helped to organize the city’s first kindergartens for Black children, taught in Cincinnati African-American public schools –including the Walnut Hills Douglass and Stowe schools—and raised money for the Home of Aged Colored Women. Since 1904, the Cincinnati Federation of Colored Women’s Clubs has ensured the civic and constitutional rights of all African Americans while meeting the needs of their city.

, OH

James W. Rankin served four consecutive terms (1971-1978) in the Ohio House of Representatives. Born and raised in Cincinnati, he graduated from Withrow High School and The Ohio State University’s School of Social Work. While working in Cincinnati’s Seven Hills neighborhood, he ran for office to “involve the disadvantaged in the governmental processes that affected their lives.” He won his first bid and served the next seven years as a state representative for the 69th House district, later the reapportioned 25th district. Representative Rankin fought passionately for civil and human rights in education and public policy. He served on the Reference, Human Resources, and Finance committees. When Rankin died of pneumonia, aged 52, the Cincinnati Enquirer proclaimed him a “Friend of the Poor.”

, OH

Walnut Hills has been home to a significant middle- and working-class Black community since the 1850s. In 1931, African American entrepreneur Horace Sudduth bought 1004 Chapel Street and then the row of buildings across Monfort, naming them the Manse Hotel and Annex. Throughout the 1940s, hotel dinner parties could move to the Federation of Colored Women’s Clubs house next door for dancing. A large addition to the Manse in 1950 created its own ballroom, 24-hour coffee shop, upgraded Sweetbriar Restaurant, and more guest rooms. It appeared in the Negro Motorist’s Green Book between 1940-1963, providing local, transient, and residential guests both catered meetings and top entertainment during the last decades of segregation. It closed in the late 1960s when the economic need for a first-class segregated hotel disappeared in the age of Black Power.

, OH

Miranda Boulden Parker lived at 2644 Marsh Avenue from 1907 to 1915. She moved into the four-family rental home with her daughters Bianca and Portia, who both worked as teachers. Miranda Parker was the widow of John P. Parker, Ripley’s Underground Railroad hero, born into slavery who famously helped more than 400 fugitives escape to freedom. In March 1914, after several vacant apartments in their Marsh Avenue home were repeatedly vandalized, daughter Bianca assumed the role as building caretaker. When she appealed to the police for help against vandals breaking windowpanes, shutters, and transoms, the police made no effort to arrest the offenders. Instead, the Health Department issued a 24-hour eviction notice. Bianca Parker sued Norwood’s Health Officer and Chief of Police unsuccessfully. The Parker family left Norwood for the more welcoming and integrated Madisonville neighborhood.

Miranda Boulden Parker lived in a home on this site from 1907(1) to 1915(2). She was the widow of Underground Railroad hero John P. Parker, who had been born into slavery. They lived in Ripley, Ohio, where John P. Parker helped more than 400 fugitives escape to freedom.(3) After his death in 1900, Miranda and their daughters Bianca and Portia, both teachers, came to Norwood. Here they rented an apartment in a four-family dwelling where Bianca became the caretaker.(4) From 1913-‘14, vandals broke over 63 windowpanes, shutters, and transoms. Bianca appealed to the police for help. Instead, the police notified the Health Department, who gave the Parkers a 24-hour eviction notice. The Parkers moved out of Norwood after unsuccessfully suing the city. (123 words)

City of Norwood, Ohio

Norwood Historical Society

The Ohio History Connection

This park was established by the City of Norwood in 1923(5) for the purpose of preventing Black Americans from owning homes here.(6) From 1907(7) to 1922(8), a four-family house on this site was rented by Black families.(9) George and Sarah Hirst lived in one of those units. On July 5, 1922, the Hirsts purchased a vacant lot next door(10) to the four-family dwelling and hired a Black contractor to build them a home.(11) White neighbors, fearing that a “Negro colony” might be developing, petitioned(12) Norwood City Council to take action.(13)(14) The Council used the right of eminent domain to seize the vacant lot from George and Sarah Hirst.(15) The Council also seized several other adjacent lots and demolished the four-family dwelling, creating Marsh Park.(16) (125 words)

City of Norwood, Ohio

Norwood Historical Society

The Ohio History Connection

, OH

Puritas Mineral Spring Company bottled and sold mineral water from the natural springs in the area. In 1894, the Cleveland and Berea Street Railway bought Puritas Springs and expanded the area into a picnic grove with a dance hall and pavilion to increase passenger traffic on the inter-urban line. Puritas Springs Park opened June 10, 1900- the first day the railways operated all the way to the entrance gates. John E. Gooding bought Puritas Springs in June 1915 and added and indoor roller rink, amusement rides, and the mighty Cyclone roller coaster. Labor Day 1958 the park closed, and on May 9, 1059 a fire destroyed many parts of the abondoned park.