, OH

In 1918, Charles Young made a desperate attempt to convince the U.S. Army that he was fit for duty. The Army’s highest-ranking Black officer, he had been medically retired and not given a command during World War I. To demonstrate his fitness, he rode 497 miles from his home in Wilberforce, Ohio, to Washington, D.C. Leaving on June 6 he made the journey in 17 days, 16 on horseback and 1 resting. Averaging 31 miles each day, he rode 45 minutes and walked 15 minutes every hour. Upon his arrival, Young met with Secretary of War Newton Baker. Pressured by the Black press and the White House, Baker hedged. He recalled Young to active duty a year later and assigned him to Camp Grant, Illinois, just five days before the end of the war.

, OH

Waterloo was home to the legendary Waterloo Wonders. Coach Magellan Hariston and his Wonder Five captured consecutive Ohio state high school Class B basketball championships in 1934 & 1935, winning 94 out of 97 games, and defeating many Class A and college teams. The 91st Ohio House of Representatives honored the Waterloo Wonders with a resolution following their second Class B State Championship win. The Wonders, known for their colorful passing show, entertained fans with their scoring ability, defense, trick passes, and hardwood antics. Hailing from a small village with a school male enrollment of only 26, the Waterloo Wonders were considered one of the greatest basketball teams ever assembled on the Ohio high school athletic scene. After high school, four of the Wonder Five played professionally as the Waterloo Wonders, ranking among the best basketball squads in the country.

, OH

Republican congressman William M. McCulloch was one of the architects of the landmark Civil Rights Act of 1964, the first of three laws to recommit the nation to the cause of civil rights in the 1960s. “Bill” McCulloch was born near Holmesville to James H. and Ida McCulloch on November 24, 1901. Raised on the family farm, he attended local public schools, the College of Wooster, and, in 1925, earned his law degree from the Ohio State University. He married his childhood sweetheart Mabel Harris McCulloch (1904-1990) in 1927, after settling in Jacksonville to start his career during the Florida land-boom of the 1920s. It was in Jacksonville that the Deep South’s racial intolerance seared him. (Continued on other side)

, OH

In 1918, Charles Young made a desperate attempt to convince the U.S. Army that he was fit for duty. The Army’s highest-ranking Black officer, he had been medically retired and not given a command during World War I. To demonstrate his fitness, he rode 497 miles from his home in Wilberforce, Ohio, to Washington, D.C. Leaving on June 6 he made the journey in 17 days, 16 on horseback and 1 resting. Averaging 31 miles each day, he rode 45 minutes and walked 15 minutes every hour. Upon his arrival, Young met with Secretary of War Newton Baker. Pressured by the Black press and the White House, Baker hedged. He recalled Young to active duty a year later and assigned him to Camp Grant, Illinois, just five days before the end of the war.

, OH

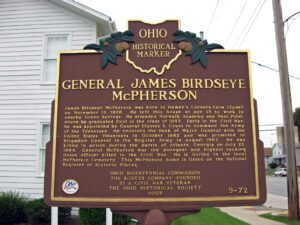

James Birdseye McPherson was born in Hamer’s Corners (now Clyde) on November 14, 1828. He left this house at age 13 to work in nearby Green Springs. He attended Norwalk Academy and West Point, where he graduated first in the class of 1853. Early in the Civil War, he was appointed by General Ulysses S. Grant to command the Army of the Tennessee. He received the rank of Major General with the United States Volunteers in October 1862 and was promoted to Brigadier General in the Regular Army in August 1863. He was killed in action during the battle of Atlanta, Georgia on July 22, 1864. General McPherson was the youngest and highest ranking Union officer killed in the Civil War. He is buried in the local McPherson Cemetery. This McPherson home is listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

, OH

In 1918, Charles Young made a desperate attempt to convince the U.S. Army that he was fit for duty. The Army’s highest-ranking Black officer, he had been medically retired and not given a command during World War I. To demonstrate his fitness, he rode 497 miles from his home in Wilberforce, Ohio, to Washington, D.C. Leaving on June 6 he made the journey in 17 days, 16 on horseback and 1 resting. Averaging 31 miles each day, he rode 45 minutes and walked 15 minutes every hour. Upon his arrival, Young met with Secretary of War Newton Baker. Pressured by the Black press and the White House, Baker hedged. He recalled Young to active duty a year later and assigned him to Camp Grant, Illinois, just five days before the end of the war.

, OH

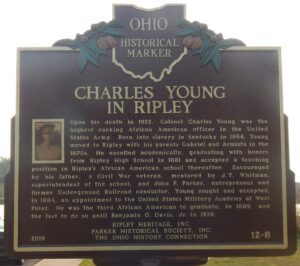

Charles Young in Ripley. Upon his death in 1922, Colonel Charles Young was the highest ranking African American officer in the United States Army. Born into slavery in Kentucky in 1864, Young moved to Ripley with his parents Gabriel and Arminta in the 1870s. He excelled academically, graduating with honors from Ripley High School in 1881 and accepted a teaching position in Ripley’s African American school thereafter. Encouraged by his father, a Civil War veteran, mentored by J. T. Whitman, superintendent of the school, and John P. Parker, entrepreneur and former Underground Railroad conductor, Young sought and accepted, in 1884, an appointment to the United States Military Academy at West Point. He was the third African American to graduate, in 1889, and the last to do so until Benjamin O. Davis, Jr. in 1936.

, OH

In 1918, Charles Young made a desperate attempt to convince the U.S. Army that he was fit for duty. The Army’s highest-ranking Black officer, he had been medically retired and not given a command during World War I. To demonstrate his fitness, he rode 497 miles from his home in Wilberforce, Ohio, to Washington, D.C. Leaving on June 6 he made the journey in 17 days, 16 on horseback and 1 resting. Averaging 31 miles each day, he rode 45 minutes and walked 15 minutes every hour. Upon his arrival, Young met with Secretary of War Newton Baker. Pressured by the Black press and the White House, Baker hedged. He recalled Young to active duty a year later and assigned him to Camp Grant, Illinois, just five days before the end of the war.