, OH

Following the national merger of the American Federation of Labor (AFL) and the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) in 1955, more than 2,000 labor delegates representing one million union members convened at the Cleveland Public Auditorium for the founding convention of the Ohio AFL-CIO in 1958. This leading labor organization achieved significant advances in the quality of life and security for working Ohioans during the second half of the twentieth century in areas of civil rights, workers’ compensation, and unemployment insurance. Its notable legislative successes include the passage of a public employee collective bargaining bill in 1983 and a voter referendum that protected worker’s compensation in 1997.

, OH

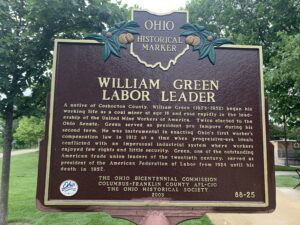

A native of Coshocton County, William Green (1870-1932) began his working life as a coal miner at age 16 and rose rapidly in the leadership of the United Mine Workers of America. Twice elected to the Ohio Senate, Green served as president pro tempore during his second term. He was instrumental in enacting Ohio’s first worker’s compensation law in 1912, at a time when progressive-era ideals conflicted with an impersonal industrial system where workers enjoyed few rights and little security. Green, one of the outstanding American trade union leaders of the twentieth century, served as president of the American Federation of Labor from 1924 until his death in 1952.

, OH

Chestnut Street Cemetery is the first Jewish cemetery in Ohio and the earliest west of the Allegheny Mountains. It was established in 1821 when Nicholas Longworth sold land to Joseph Jonas, David I. Johnson, Morris Moses, Moses Nathan, Abraham Jonas, and Solomon Moses for $75 as a “burying ground.” Benjamin Lape (or Leib) was the first buried there with Jewish rites. The purchase of the original plot marks the beginning of an organized Jewish community in the Queen City. Chestnut Street Cemetery, although enlarged by adjacent purchases, closed in 1849 when cholera ravaged the city and filled available space. In all, there are approximately 100 interments on the site. Jewish Cemeteries of Greater Cincinnati maintains Chestnut Street Cemetery as well as many other Jewish cemeteries in the region.

, OH

Walnut Hills has been home to a significant middle- and working-class Black community since the 1850s. In 1931, African American entrepreneur Horace Sudduth bought 1004 Chapel Street and then the row of buildings across Monfort, naming them the Manse Hotel and Annex. Throughout the 1940s, hotel dinner parties could move to the Federation of Colored Women’s Clubs house next door for dancing. A large addition to the Manse in 1950 created its own ballroom, 24-hour coffee shop, upgraded Sweetbriar Restaurant, and more guest rooms. It appeared in the Negro Motorist’s Green Book between 1940-1963, providing local, transient, and residential guests both catered meetings and top entertainment during the last decades of segregation. It closed in the late 1960s when the economic need for a first-class segregated hotel disappeared in the age of Black Power.

, OH

By 1922, the Ambler Realty Company of Cleveland owned this site along with 68 acres of land between Euclid Avenue and the Nickel Plate rail line. Upon learning of the company’s plans for industrial development, the Euclid Village Council enacted a zoning code based on New York City’ building restrictions. Represented by Newton D. Baker, former Cleveland mayor and U.S. Secretary of War under Woodrow Wilson, Ambler sued the village claiming a loss of property value. In 1926, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in favor of Euclid and upheld the constitutionality of zoning and land-use regulations by local governments. The federal government eventually acquired the Ambler site during World War II to build a factory to make aircraft engines and landing gear. From 1948 to 1992, the site was used as a production facility by the Fisher Body Division of General Motors.

, OH

Players of the Cleveland Browns gathered eleven Black professional athletes and future mayor Carl Stokes to discuss with boxer Muhammad Ali (January 17, 1942-June 3, 2016) his refusal to serve in the Vietnam War. After their private meeting on June 4, 1967, the twelve men decided to “support Ali on principle” and held a lengthy national press conference. The boxer, considered the “greatest heavyweight of all time,” garnered national scorn and paid a high price for his stance. Ali was arrested, found guilty of draft evasion, his passport confiscated, titles stripped, and U.S. boxing licenses suspended. The men in attendance also faced condemnation and threats. In 1971, the Supreme Court unanimously overturned Ali’s conviction. The Cleveland Ali Summit is considered “one of the most important civil rights acts in sports history.”